Home > Controversy on Authorship > The Possible Authors >Rafael Urzúa Arias

As previously mentioned, a single one of the reviewed sources points out engineer Rafael Urzúa Arias as the author of the project of the Workshop-Dormitory of López Cotilla in the city of Guadalajara: the Historical and Biographical Encyclopedia of the University of Guadalajara. There was an attempt to contact professor Juan Real Ledezma, responsible of said publication, with the intention of understanding the base for such affirmation. However, it was not possible to arrange an interview, and the bases for this assertion remain unknown.

The estimated dates for the realization of the project of the Workshop-Dormitory (second semester of 1936), could be favorable to Urzúa, since both he and Orozco lived in the city of Guadalajara at this time (unlike Barragán). However, it seems relevant that, even though the painter and Urzúa had a close and frequent relationship, there is not a single mention of Urzúa by Orozco in any of the reviewed literature. In a similar manner, no reference to a possible participation of Urzúa was found during the revision carried out at the Archive of the Rafael Urzúa Fund. This archive is the documental collection of the work of engineer Urzúa, currently safeguarded by the Secretary of Culture of the State of Jalisco.

With the intention of contrasting the aesthetic language of Urzúa with that used in the López Cotilla St Workshop-Dormitory, it is convenient to make a brief review of the evolution of different architectural movements through which the engineer passed since he graduated the Free School of Engineering in 1925, until the date when the project for the Workshop-Dormitory was carried out, in 1936. From said review, the possibility of his participation or authorship will be evaluated.

During the Porfiriato, the influence of French architecture predominated, according to the ideals and expectation of the upper class of this time. In Orozco’s words, Architecture came to be a copy of French chalets and chateaux1. After the Revolution architecture, along with other artistic expressions, turned inwards, looking to consolidate an own and national language. In this context, movements such as Neocolonialism and Neoindigenism surged, searching for their identity in the past and cultural diversity of the country.

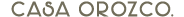

This ideological transformation meant leaving behind the idealization of European canons, but, in a way, tried to tackle XXth century problems with XVIIIth century solutions. In an otherwise notable manner, Urzúa carried out several neocolonial style projects. His project for the Museum of Colonial art, carried out in 1925 (the same year he graduated the Free School of Engineering), stands out. Even though it was not built, it evidences Urzúa’s extraordinary capacity of understanding different architectural styles.

Fig. 1. Project for the facade for the Museum of Colonial Art, by Rafael Urzúa.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

The boundaries of Neocolonialism and Neoindigenism gave way to the search for a national architecture. In this context, the Escuela Tapatía de Arquitectura (Guadalajara School of Architecture) emerges. Its participants include Luis Barragán, Pedro Castellanos, Ignacio Díaz Morales and Rafael Urzúa. It is important to clarify that the Escuela Tapatía de Arquitectura was not a current nor a stylistic movement, but rather, the search of a group of young professionals with shared origins and inclinations.

Without a doubt, Luis Barragán was the leader of this group, since his desire to learn and his curiosity to see what was happening in other places took him to set upon several travels to foreign countries. This allowed him to stay current on tendencies and avant-garde of international architecture. The discoveries he made a great impact on his fellow colleagues, and would mark the way of the Escuela Tapatía.

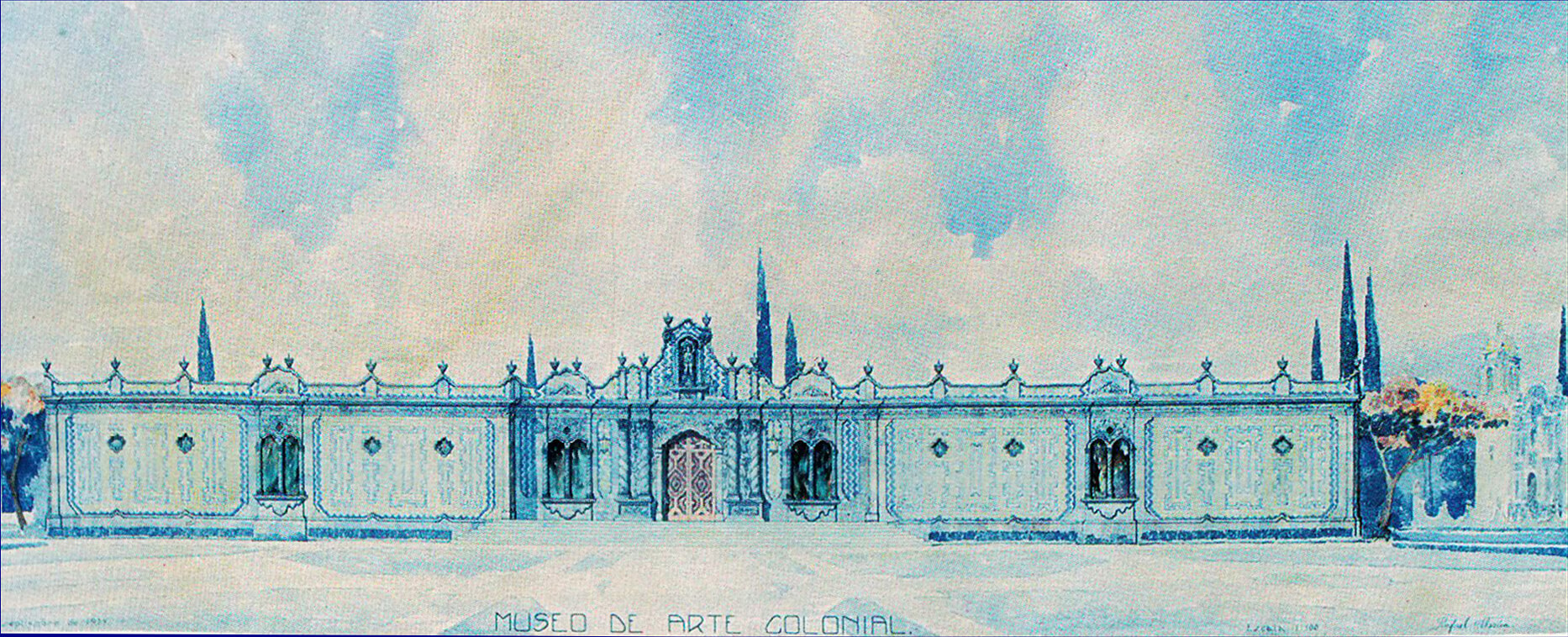

The first rupture of the Escuela Tapatía de Arquitectura was with Neocolonial style, predominant at the time, and surging from the influence of Ferdinand Bac. It reached Guadalajara trough Barragán, who gave Urzúa and Díaz Morales the books Les Jardins Enchantés and Les Colombières, of Bac’s authorship, which he had brought from his first travel to Europe in 1925.

The architectural concepts and the garden designed applied in Bac’s works fascinated Barragán, and he passed that enthusiasm on to his colleagues. The influence of Bac was one of the bases for the origin of Regionalism in the city, which borrows concepts and elements from Mediterranean and Moorish architecture.

Fig. 2. Ilustration by Ferdinand Bac.

Les Jardins Enchantés. Ferdinand Bac.

Fig. 3. Project for a pavilion, proposed for the Revolution Park, by Rafael Urzúa. Note the similarities with Bac’s illustration, including the use of arches, textures and water.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

Rafael Urzúa carried out, with great artistry, numerous regionalist projects, in which Ferdinand Bac’s influence is evident. His projects for homes stand out, as well as the project for the access of Agua Azul Park (1934, demolished) and his entry for the Revolution Park contest, carried out the same year. Bac´s influence is still present in the last works he carried out in his hometown, Concepción de Buenos Aires, Jalisco.

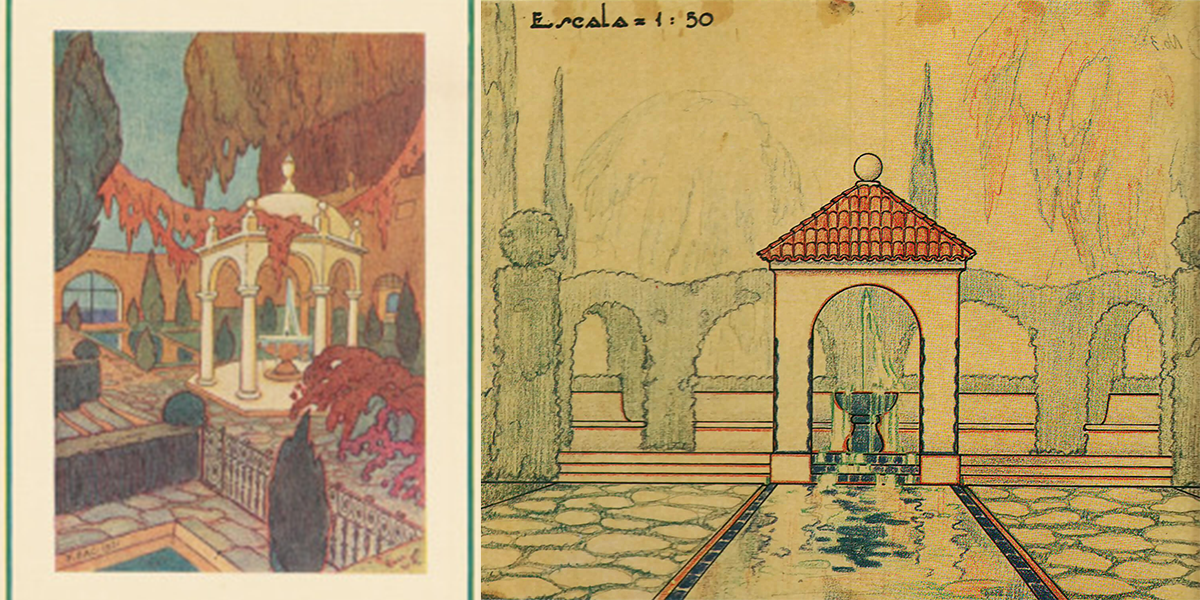

Fig. 4. Facades of houses for Carmen Becerra Urzúa. Rafael Urzúa Arias.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

Fig. 5. View of the house and sanatorium Jesús Gutiérrez Casillas.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

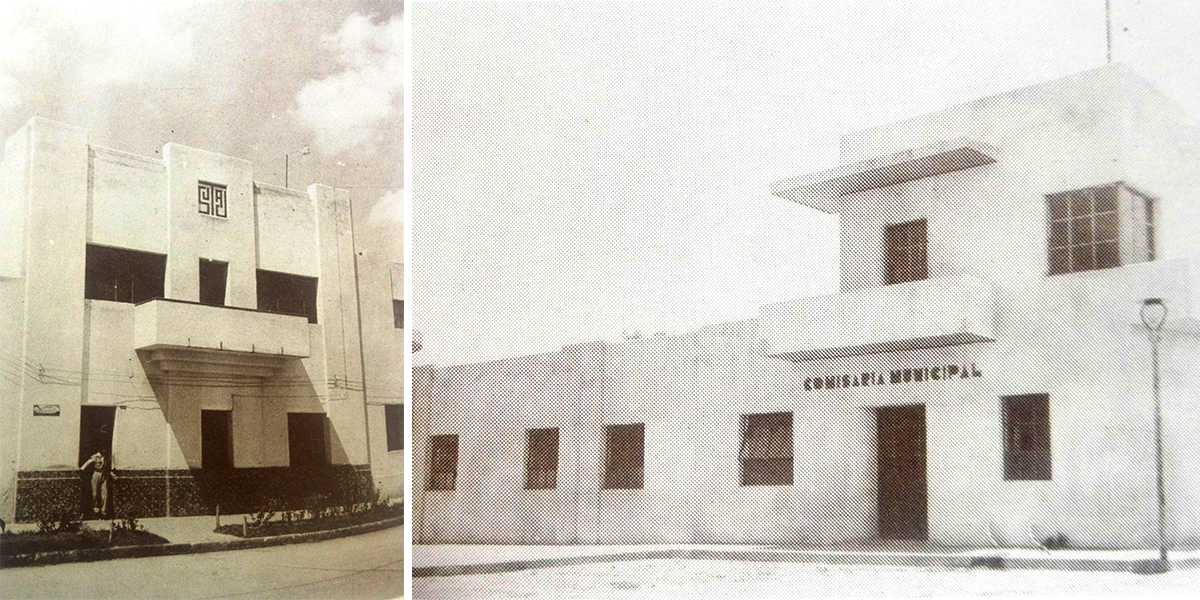

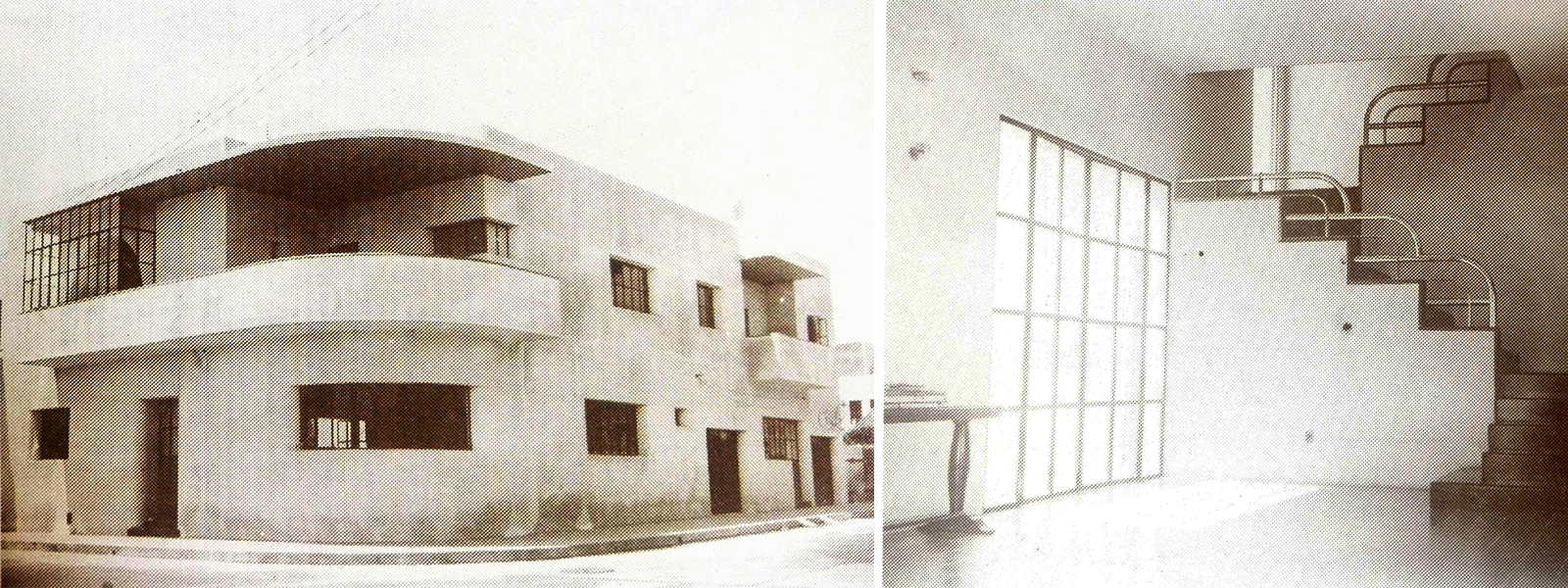

For the second half of the thirties decade of last century, also by Barragán’s influence, Urzúa steps back, momentarily and to a certain extent, from regionalist ideas, towards notable proposals in Art Deco and Modern architecture. From this period, it is convenient to observe the projects of the SUTAJ building, the market, school and police station Atemajac ensemble, and the house for Mr. Rogelio Rubio, at the corner of Marcos Castellanos and Pedro Moreno streets, facing Revolution Park.

From the two works mentioned above, Urzúa uses with great success the formal language of Art Deco. However, in the house for Mr. Rogelio Rubio (1935), even though he continues using some Art Deco elements (round corners, the design of the interior lamps, and the furnishing and design of the main staircase), a clear evolution towards modern architecture is clearly visible, with a tendency to simplify architectural shapes, and putting aside ornamental elements as much as possible.

Fig. 6. Facade of the SUTAJ building.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

Fig. 7. Police station of the Atemajac ensemble.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

Figs. 8 and 9. House for Rogelio Rubio. This is a work in the style of European functionalism, with corbusiana influence. It includes elements of Art Deco, as can be seen on the staircase.

Rafael Urzúa, arquitecto. (Lanzagorta Vallín, 2000)

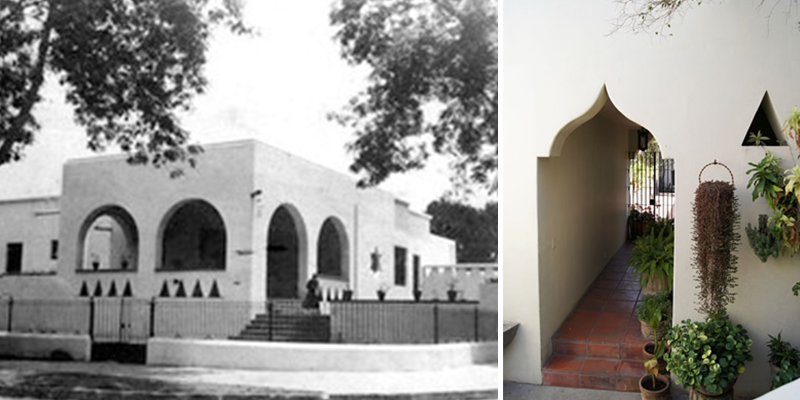

Without a doubt, his most outstanding and influential work is the house for Doctor Luis Farah, located at the northeast corner of Vallarta avenue and Simón Bolivar St, in Guadalajara, dating from year 1936 (same year as the Workshop-Dormitory was designed). Urzúa shows us in the Farah House his creativity and mastery, solving the project through a fusion of different influences and architectural concepts. Even though it is a work of remodeling, it achieves an extraordinary synthesis of Modernism and Regionalism. It integrates the cleanness in its composition from the modern movement with some refined elements of Regionalism, such as the façade’s triangle motives, and from Moorish architecture, such as the ogee arch and the star-shaped window, among others.

Figs. 10 and 11. Farah House. Note the ogee arch in the hallway. Urzúa reaches a greater use of Modernism, without, however, reaching the formal austerity and abstraction of the López Cotilla Home-and-Studio.

Casa Haus. https://casahaus.net/quedamos-para-tomar-algo/

https://ourvoicesgdl.wordpress.com/2014/04/12/regional-architecture-in-guadalajara/

Urzúa was a friend, collaborator, and, possibly, the first follower of Luis Barragán. He worked at his firm since he graduated the Free School of Engineering until Barragán left Guadalajara to move to Mexico City in 1935. In 1929, he started to work from at his own firm, alongside his collaboration with Luis Barragán. He was doubtlessly the most talented member of the Escuela Tapatía de Arquitectura, as well as the one who put in practice the ideas brought by Barragán from his travels with most enthusiasm. He was a quick learner, and he reinterpreted concepts according to his own vision and criterion.

It must be mentioned that Urzúa was a prolific designer, carrying out 131 own works and projects, according to the reviewed Urzúa Fund catalogue2. He was always aware of architecture trends, and had an extraordinary skill in creating works in different styles, without losing, because of this, quality in his designs.

If Urzúa’s oeuvre is reviewed meticulously, it is evident that, throughout it, he experiments with different architectural styles. In addition, it can be clearly noticed that his formal and aesthetic language was not related to architectural abstraction (noticeable influence in the Workshop-Dormitory), but rather, with Regionalism as an integrator of influences and styles. His most brazen approaches to modern architecture are still far from the composition, strength, geometry and aesthetic unity of the Workshop-Dormitory, and, even though they are relevant for the city’s history of architecture, do not justify the conclusion that he designed the building.

Most of his work are rather meticulous projects, with an accessible and polished aesthetic, which were, and still are, valued by their users (unlike city authorities that have allowed the demolition of many of them). His works, however, do not show conceptual nor technical innovation. Urzúa was a practical man who, unlike Barragán, did not concern himself with creating an architecture that would break away from the existing.

What can be concluded with certainty is that, even though Urzúa was not responsible for the design of the Workshop-Dormitory, he was a crucial actor for its materialization. Given his closeness to Barragán and Orozco, it is very likely that he supported the latter with his contact network in the local construction sphere (workforce, material providers, contractors, etc.). It would not be too risky to think that Urzúa himself, or his firm, carried out the executive project of the Workshop-Dormitory.