The area surrounding the property where Orozco built his Workshop-Dormitory of López Cotilla St adjoins the west limit of the Historical Center of the city of Guadalajara. Throughout the years, this area has undergone multiple transformations that, for better or worse, have traced its urban image and identity.

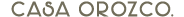

Fig. 1. Map of the city of Guadalajara in 1930, five years before Orozco´s arrival.

https://bit.ly/2L3XAiT

During the viceregal period, these grounds were used as the orchard of the Convent of El Carmen, a male cloister annexed to the Temple of El Carmen, erected by the Order of the Discalced Carmelites, which was located at the westernmost end of the city. This important ensemble began its construction between 1680 and 16901.Its design is attributed to the Spanish architect Juan Bautista de la Mora. The construction of the complex concluded in the year 1758.

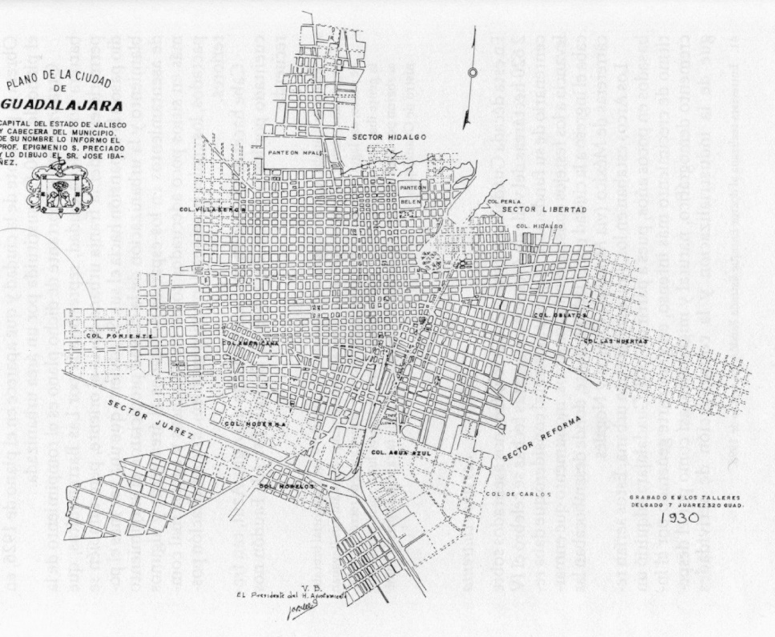

Fig. 2. Map of the city of Guadalajara, 1899, East-up. The property correspondent to the orchard of the Convent of El Carmen is located at the west. INEGI Historical Archive.

Fig. 3. Detail of map of Guadalajara, 1800. The legend reads “16 El Carmen”. Municipal Archive of Guadalajara.

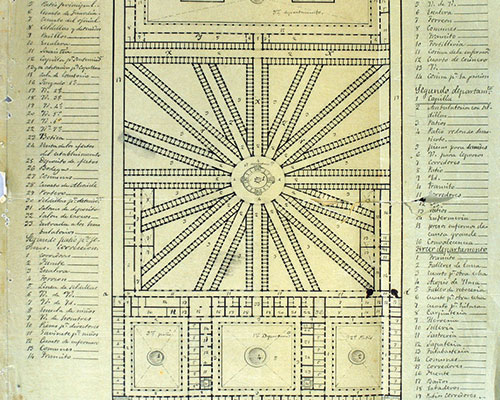

Between the years of 1843 and 18452, the authorities of the Convent of El Carmen donated its orchard grounds to the Government of Jalisco. The State Penitentiary, also known as the Penitentiary of Escobedo (in memory of the State governor José Antonio Escobedo, who ordered its construction) was built on said property. American architect Carlos Nebel projected the Penitentiary. Don José Ramón Cuevas was in charge of its construction. Later, architect Valentín Méndez took over the construction, and, finally, engineer David Bravo3. The construction began in the year of 1845. It occupied the blocks encompassed by the current streets of Pedro Moreno, Puebla, Enrique Díaz de León Ave, and López Cotilla. The works concluded in 1875.

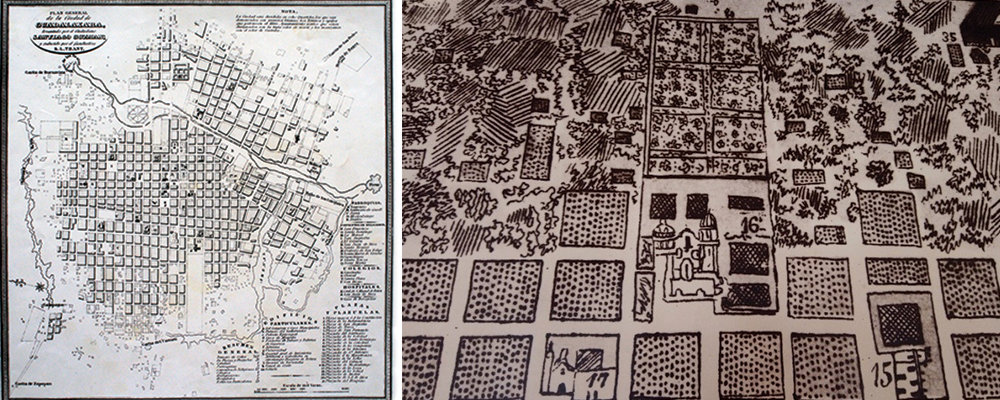

The project of the Penitentiary of Escobedo was inspired in Bentham’s Panopticon, a model where architecture took an active role in the punitive model. With a neoclassical style, it counted with a clock in the center of its pediment, an element of great modernity at the time.

Fig. 4. Portico of the Penitentiary of Escobedo.

Fig. 5. Elevated view of the Penitentiary of Escobedo. EL INFORMADOR.

https://bit.ly/31Tdsem

It occupies eight blocks, and is distributed in the following manner: at the front, a great square patio, surrounded by magnificent corridors, which form first and second floors, and give entry to all the offices of the judicial administration; then follow ten and six ambulatories or rather extensive corridors, that reunite in the shape of rays of a star in a common courtyard, having each forty or fifty cells and its special patio; at one side, are the women´s prison and the quarters for the guard; in the high parts, there is a photograph, to take the pictures of criminals.

In the rear part of the building are the section for workshops, the bathroom, the garden, and everything concerning such establishment.

(…) Six or eight soldiers are enough to watch so many inmates. 4

Fig. 6. Floorplan of the State Penitentiary, signed by Valentín Méndez. Document by Mtra. Alma Yolanda Valeriano Sánchez.

https://bit.ly/2MXcJW0

Between the years of 1860 and 1861, the building of the Convent was taken by the Liberal Forces as a Headquarter, who took over the property to put it in the hands of the Government of the State of Jalisco, through the application of the Reform Laws. Around the same date, the Penitentiary, still unfinished, became barracks, prison, and fortress5.In the year of 1861, the Mayor Temple of the Convent was demolished6.

In the year of 1948, during the westward prolongation of Juárez Ave, a part of the original Convent building was demolished, in one of the many modernizing efforts that our authorities have misguidedly undertaken.

Fig. 7. Photograph of the partial demolition on the Ex Convent of El Carmen, dated July 1948.

https://bit.ly/2ZCIqWe

In the year of 1914, in order to prolong Escorza St southwards, authorities carried out the first mutilation of the Penitentiary of Escobedo. By doing so, they divided the property of said Penitentiary in two, and the western section was divided, in turn, into two segments.

On these two parcels, engineer Alfredo Navarro Branca designed and constructed two schools, one located south of Juárez Ave, that took the name of “Reforma” (present-day Hall of the University of Guadalajara), and another north of said Avenue, which was named “Constitución”. The latter would later operate as the Music School of the University of Guadalajara. This beautiful building was demolished in the year of 1980, by the rector of the University Jorge Enrique Zambrano Villa, who was, paradoxically, an architect.

Figs. 8 and 9. Demolition of Constitución School, also known as the Music School.

Fig 8. Municipal Archive of Guadalajara.

Fig. 9. Gaceta de la Universidad de Guadalajara.

https://bit.ly/2x4hx19

If these stories of the destruction of the area’s heritage were not enough, in the year of 1932, the State governor, general and lawyer Sebastián Allende ordered the demolition of the Penitentiary of Escobedo. The demolition works concluded the following year, making it the first Latin American Panopticon prison to be completely demolished7.7

The beautiful building was destroyed, since, in the eyes of the authorities, a penitentiary was not an adequate use for the “wealthy and western” part of the city. Disregarding the misguidedness said criterion regarding the use of the building, it can be noted that reutilizing the building with a different function would have sufficed, and this important property would have been rescued.

The fact is that the penitentiary was demolished, and on the grounds where it had stood, a new development was projected, which would count with a great park as an anchor space, and residential lots that would be put on sale.

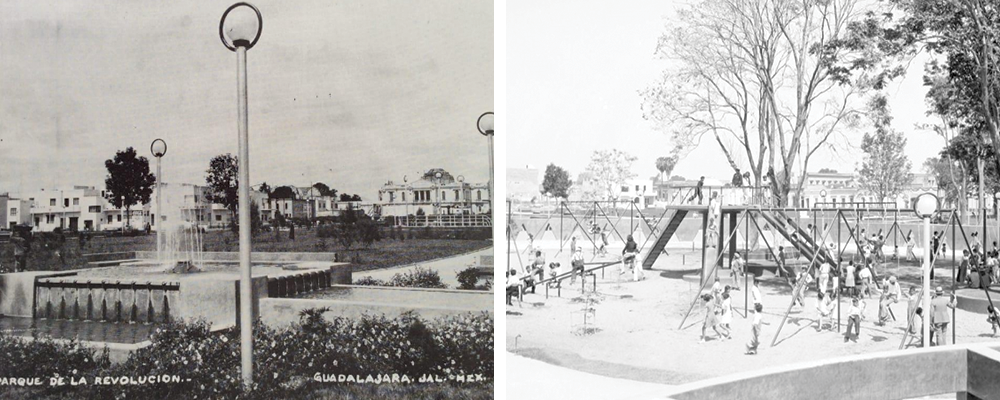

Fig. 10. Photograph Revolution Park. On the left, the original project’s roundabout.

https://bit.ly/2FlZDLB

Fig. 11. View of Revolution Park, year 1954. Municipal Archive of Guadalajara.

The Government of the State called a contest for the design of said park. Numerous professionals participated, among which two participants stand out: engineer Rafael Urzúa and architect Luis Barragán. The latter participated in association with his elder brother, engineer Juan José Barragán Morfín.

The Barragán brothers won the contest, and they were also assigned the construction of the park. The State governor Sebastián Allende inaugurated it on February 28, 1935.

Fig. 12. View of the “water games” of the Revolution Park and some modernist houses in the background. Espacio, color y formas en la Arquitectura. Olarte Venegas et. al. 322

Fig. 13. Playground of Revolution Park. El Siglo de Torreón El Siglo de Torreón.

https://bit.ly/2FlIbH0

Throughout the little more than eight decades since its construction, the Revolution Park, better known by locals as Parque Rojo (Red Park) in account of its floor of polished red cement, has undergone at least four interventions that have modified the original project.

Fig. 14. Bird’s eye view of Revolution Park in 1958. Municipal Archive of Guadalajara.

Despite the terrible history of destruction of built heritage that has taken place in this centric area, there are still numerous properties whose protection and conservation are of great importance.

Few areas in Guadalajara make up such a homogenous urban environment and concentrate so many examples of proper architecture in such a small area. The most prominent engineers and architects of the city in the thirties designed and built houses in the area: Rafael Urzúa, Ignacio Díaz Morales, Castellanos y Martínez Negrete, Luis Barragán, Barragán y Garibi, Luis Ugarte, Francisco Labastida Izquierdo, Aurelio Aceves, Enrique González Madrid and Miguel Aldana Mijares, among many others.

Even today, many of these buildings are in danger of disappearing, thanks to the little or completely lacking protection granted by legal regulations, and to a misled redensification policy that, unbelievably, our authorities are endorsing even in immovable heritage zones.

Just in the last six months, two valuable buildings have been demolished on López Cotilla St (street numbers 795 and 831/843). Both demolitions were carried out, allegedly, without permission, leaving only the facades standing. One of these plots was abandoned, and the other is used as the parking lot of a seafood restaurant. Is this the future that awaits the rest of the buildings in the area?

In the year 2012, the works of restoration of the Workshop-Dormitory for José Clemente Orozco were carried out. Said restoration, along with the investigation that preceded the present web site, aim towards valuing the building as a historical document and as an architectural legacy. Great hope is maintained that this small effort will inspire other citizens and actors to achieve the preservation of this area that contributes such a high value and identity for the city.

1. Secretaría De Cultura del Estado de Jalisco. Ex Convento Del Carmen. (Gobierno Del Estado De Jalisco, 2014.)

2. Secretaría de Cultura. Ex Convento Del Carmen.

3. Arturo Chávez Hayhoe. Guadalajara de Ayer. 8.

4. Ignacio Martínez en Museo Claudio Jiménez Vizcarra. La Penitenciaría de Escobedo.

5. Chávez Hayhoe, Guadalajara de Ayer. 33

6. Alma Yolanda Valeriano Sánchez. Reseña del Diseño Arquitectónico y Organización del Espacio Penitenciario de lo que fue la Penitenciaría de Escobedo.

7. Carlos Aguirre. Apogeo Crisis y Transformación del Panóptico Iberoamericano: Apuntes para la Historia de un Modelo Arquitectónico.